The bolted pressure switch (BPS) once occupied a central role in 480-V distribution systems across industrial, commercial, and institutional facilities. Known for its rugged construction and ability to withstand high fault currents, the BPS was a workhorse of mid-20th-century, low-voltage power distribution. By using spring-driven mechanical force to bolt contacts together, the BPS ensured a low-impedance path for current flow, even under heavy load conditions.

However, the BPS was designed primarily as an isolating device rather than a true switching or protective device. While it could reliably carry current, it could not safely interrupt load or fault current. As a result, operators were expected to de-energize systems prior to operation — a practice that relied heavily on human factors and was not always followed.

In the modern context of arc flash awareness, OSHA regulations, and NFPA 70E compliance, the limitations of the BPS are clear. High incident energy levels, lack of protective integration, and mechanical aging of these devices present risks to personnel and equipment. In contrast, today’s breaker technologies — molded-case circuit breakers (MCCBs) and insulated-case circuit breakers (ICCBs) — provide integrated protection, fault-interrupting capability, and arc flash mitigation features that were not possible in the BPS era.

HISTORY OF THE BOLTED PRESSURE SWITCH IN 480-V SYSTEMS

The bolted pressure switch emerged in the 1950s and 1960s as an answer to the limitations of earlier knife switches and fused disconnects. At the time, the electrical industry was expanding rapidly as hospitals, universities, factories, and data centers required robust distribution systems operating at 480 Volts.

The BPS quickly gained adoption because it could:

- Withstand short-circuit currents until upstream fuses cleared

- Provide visible isolation, useful for maintenance and lockout/tagout (LOTO)

- Operate without oil or gas interrupters, simplifying maintenance

Common installations included:

- Service disconnects between utility transformers and main switchboards

- Feeder switches supplying large motor control centers

- Institutional and industrial distribution panels

Despite its prevalence, the BPS was never designed for load-break duty. Unlike breakers, it did not extinguish arcs in a controlled manner, leaving operators exposed if switching was attempted on energized systems.

TECHNICAL DRAWBACKS OF THE BOLTED PRESSURE SWITCH

No Load-Break Capability

The BPS relies on a bolted mechanical connection. Opening the device under load produces uncontrolled arcs that can persist until interrupted by upstream protection. Modeling based on IEEE Std. 1584, IEEE Guide for Performing Arc-Flash Hazard Calculations, shows that even a modest 480-V arc can release energy over 20 cal/cm² within a few cycles. Without arc chutes, vacuum bottles, or magnetic blowout features, the BPS is inherently unsafe for load switching.

Mechanical Wear and Degradation

- Springs lose elasticity, reducing contact force

- Lubricants dry out, increasing mechanical friction

- Contact erosion increases resistance, generating heat at the interface

Elevated contact resistance can lead to localized heating, insulation breakdown, and eventual phase-to-phase or phase-to-ground faults. Many BPS failures manifest as catastrophic bus faults during operation.

Limited Protective Functionality

The BPS provides isolation only — no overcurrent or short-circuit protection — and ground fault capabilities are through external GFR relays to a shunt trip device. Coordination must rely on external fuses or upstream breakers. This introduces three issues:

- Lack of adjustability compared to solid-state circuit breaker trip units

- Poor selectivity in complex feeder systems

- Slower clearing times at moderate fault currents

Arc-Flash Hazards

The BPS era predated the formal recognition of arc flash hazards. NFPA 70E, Standard for Electrical Safety in the Workplace (first issued in 1979) and IEEE 1584 (2002) formalized methods to calculate and mitigate arc energy. Many legacy 480-V BPS lineups test at incident energy levels above 30–50 cal/cm², requiring PPE Category 4 and higher, which are impractical for maintenance.

The incident energy equation per IEEE 1584:

Where:

- E = incident energy (cal/cm²)

- Iarc = arcing current (kA)

- t = clearing time (s)

- D = working distance (mm)

- k = empirically derived constant

Since clearing time (t) is directly proportional, the slow clearing times associated with fuse/BPS systems result in disproportionately high incident energy values.

Aging Infrastructure and Parts Obsolescence

Most BPS devices in service today are more than 15 to 40 years old. Some manufacturers no longer provide replacement parts, and insulation systems have often exceeded their rated lifespans. Due to the aging equipment and the immense amount of spring pressure and force experienced during an operation, the typical BPS mechanism and internal parts suffer a higher failure rate. Continued operation represents safety, reliability, and liability issues.

TRANSITION TO MODERN BREAKER TECHNOLOGIES

By the late 20th century, MCCBs (UL 489) and ICCBs (UL 1066) replaced BPS systems in most new construction. Breakers integrate switching and protective functionality into a single device, eliminating the need for separate fuses.

Key technical advantages include:

- Load and fault interruption. Arc chutes and magnetic blowout paths extinguish arcs in less than 3 cycles.

- Trip unit integration. Long-time (L), short-time (S), instantaneous (I), and ground-fault (G) elements can be tailored to system coordination.

- Electronic trip units. Adjustable curves allow coordination studies per ANSI C37.13/16, Low-Voltage AC Power Circuit Breakers Used in Enclosures, which was superseded by IEEE Std. C37.13 IEEE, Standard for Low-Voltage AC Power Circuit Breakers Used in Enclosures.

- Reduced maintenance. Self-contained operating mechanisms with limited moving parts.

- Arc-flash mitigation. Zone-selective interlocking (ZSI), arc flash maintenance switches, and arc-resistant enclosures significantly reduce incident energy.

These features make breakers far more suitable for compliance with NFPA 70E and OSHA 1910 Subpart S Electrical.

INCIDENT ENERGY AND ARC FLASH CONSIDERATIONS

One of the most important reasons to replace legacy BPS systems is the opportunity to reduce incident energy levels.

- Legacy BPS systems. Clearing times governed by upstream fuses result in high arc flash energies (20–50 cal/cm²).

- Modern breaker systems. Faster clearing times reduce incident energy to <8 cal/cm².

- Maintenance mode. Temporarily decreasing instantaneous pickup further reduces incident energy to <4 cal/cm², often within PPE Category 1.

REAL-WORLD EXAMPLE: FUSE/BPS TO BREAKER UPGRADE

A 480-V distribution system fed by a 2,500-kVA transformer (5% impedance, infinite bus primary) originally used a fused BPS.

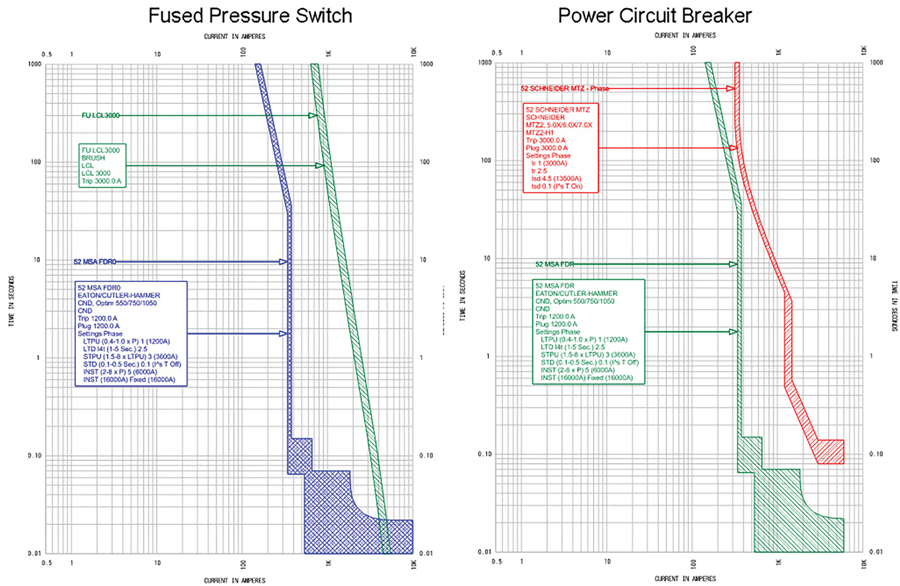

The time-current curves (TCCs) reinforce this result (Figure 3):

- Fuse curve: slow clearing at moderate faults (hundreds of ms)

- Breaker (normal mode): faster clearing with short-time trip

- Breaker (maintenance mode): instantaneous clearing (<50 ms), dramatically reducing arc flash energy

The differences between the fused bolted pressure switch (left) and the power circuit breaker (right) are clear (Figure 4).

The fused BPS relies on fuse characteristics, resulting in longer clearing times at moderate fault levels — in the range of tenths to several seconds — before the fuse melts and clears. This extended duration allows more fault energy to be released, which translates directly into higher incident energy levels and greater stress on downstream equipment.

In contrast, the power circuit breaker incorporates electronic trip units that can act in the instantaneous region, clearing faults in tens of milliseconds at similar current levels. This faster clearing dramatically reduces arc flash exposure to personnel and limits damage to the distribution system, often making the difference between minor repairs and major equipment replacement.

The implication is also clear: While the BPS can carry and withstand fault current, only the breaker provides the controlled, rapid interruption needed to align with modern safety standards and minimize both personnel risk and equipment downtime.

Impact

- Personnel safety improves dramatically, moving from Category 4 PPE to Category 1–2.

- Equipment stress is reduced, leading to minor repairs rather than catastrophic failures.

- Operational uptime is preserved, avoiding costly downtime from equipment replacement.

LEGACY SYSTEMS AND MODERNIZATION OPTIONS

Facilities with BPS equipment typically face three options:

- Maintain. Continue operating with inspections, lubrication, and training. Risks remain high.

- Retrofit. Replace BPS switchboard cells with breaker retrofits. Preserves structure, lowers cost, and reduces incident energy.

- Replace. Completely replace with breaker-based switchgear. Highest upfront cost but ensures compliance, safety, and long-term reliability.

An added benefit of modern circuit breakers is that programming for remote operation is possible, further enhancing employee safety by ensuring that personnel are not positioned directly in front of the gear when opening or closing the breaker. While bolted pressure switches can also be adapted for remote operation through third-party devices such as ArcSafe’s RSA-135 remote operator (Figure 5), these solutions may not immediately be available for urgent switching requirements and often come at an additional cost.

Modernization programs are often justified by reduced PPE requirements, lowered insurance liability, and prevention of downtime losses from major equipment failures.

CONCLUSION

The bolted pressure switch represented an important stage in the evolution of low-voltage distribution systems, bridging the gap between crude mechanical disconnects and the sophisticated protective devices used today. For decades, the BPS served facilities reliably by providing a means of isolating circuits and withstanding the thermal and mechanical stresses of high short-circuit currents. In its era, the BPS was considered a rugged, dependable, and relatively low-maintenance solution.

However, its design limitations are unmistakable when viewed against modern requirements. The BPS lacks the ability to interrupt load safely, instead relying on external fuses or upstream devices for fault clearing. This dependence not only limits coordination but also prolongs clearing times, directly leading to higher incident energy levels. Furthermore, decades of service have left many BPS installations suffering from mechanical wear, degraded insulation, and obsolescence, with spare parts increasingly unavailable. Combined with the fact that these devices were never engineered with arc flash mitigation in mind, continued operation of BPS lineups exposes personnel to hazards well above acceptable thresholds under NFPA 70E and IEEE 1584 guidance.

By comparison, modern molded-case (MCCB) and insulated-case (ICCB) circuit breakers embody the integration of switching, protection, and safety functions in a single device. These breakers provide precise trip unit coordination per ANSI C37, instantaneous clearing capabilities that drastically reduce arc flash exposure, and compatibility with advanced safety features such as zone-selective interlocking (ZSI) and maintenance mode arc flash reduction switches. Breakers also support remote operation and racking, keeping personnel outside the arc flash boundary and aligning with OSHA’s emphasis on minimizing exposure through engineering controls.

The benefits extend far beyond personnel safety. Faster fault-clearing significantly reduces the energy let-through to the system, limiting damage to bus structures, cables, and connected loads. Where a fault cleared by a fuse/BPS might result in severe damage requiring weeks of repairs and production downtime, the same fault cleared by a breaker can often be followed by moderate repairs and rapid return to service. In this sense, breaker modernization is as much about operational continuity and asset preservation as it is about compliance and worker protection.

Ultimately, the transition from bolted pressure switch technology to modern breakers is not a matter of convenience or incremental upgrade. It is a safety-critical modernization strategy that directly impacts personnel well-being, equipment reliability, and facility productivity. For organizations still operating legacy BPS lineups, proactive retrofitting or replacement is no longer optional but essential. Such upgrades reduce risk exposure, ensure compliance with NFPA, IEEE, ANSI, and OSHA standards, and future-proof facilities against the increasingly stringent demands of electrical safety. By investing in breaker-based systems, facility owners protect not only their workforce but also the operational resilience of their entire electrical infrastructure.

REFERENCES

- IEEE Std. 1584, IEEE Guide for Performing Arc-Flash Hazard Calculations.

- NFPA 70E, Standard for Electrical Safety in the Workplace

- ANSI C37.13/16 ANSI C37.13/16, Low-Voltage AC Power Circuit Breakers Used in Enclosures, (superseded by IEEE Std. C37.13 IEEE, Standard for Low-Voltage AC Power Circuit Breakers Used in Enclosures.

- OSHA 1910 Subpart S Electrical

Matthew Wallace is Vice President of CBS Field Services, a NETA Accredited Company, and has held his current position for two years.A graduate of Iowa State University and the U.S. Navy Nuclear Program, he has more than 25 years of experience in the electrical testing and commissioning industry. Matthew is a NETA Level 3 Certified Technician.

David Muir serves as Business Development Manager for Advanced Electrical & Motor Controls, part of Group CBS, a leading network of companies specializing in low- and medium-voltage power distribution solutions. With more than 30 years of industry experience, David has built a reputation for helping clients achieve reliability, safety, and cost efficiency through innovative switchgear, motor control, and circuit breaker solutions. His deep technical knowledge and relationship-driven approach make him a trusted partner to OEMs, utilities, and industrial customers alike.