This issue’s theme brings up a question frequently asked by NETA technicians: “When does troubleshooting end and when does repair begin?” This question is often paired with “What does 70E say about troubleshooting and repair?” We hope to make things clear for everyone in the field.

To begin, look at the definition of “working on” (energized electrical conductors and circuit parts) from Article 100 of NFPA 70E:

Working On (energized electrical conductors or circuit parts).

Intentionally coming in contact with energized electrical conductors or circuit parts with the hands, feet, or other body parts, with tools, probes, or with test equipment, regardless of the personal protective equipment (PPE) a person is wearing. There are two categories of “working on”: Diagnostic (testing) is taking readings or measurements of electrical equipment with approved test equipment that does not require making any physical change to the equipment; repair is any physical alteration of electrical equipment (such as making or tightening connections, removing or replacing components, etc.).

There is a lot going on in this definition. The first sentence begins with “Intentionally coming in contact ….. with the hands, feet, or other body parts ….” So in this definition, contact is not accidental, but intentional with any part of the body. This separates it from unintentional contact (incident) or any type of equipment failure. That sentence continues “with tools, probes, or with test equipment, regardless of the personal protective equipment (PPE) a person is wearing.” This makes it clear that using voltage testers or any other type of test equipment is included, and PPE doesn’t change this; you’re still working on energized electrical conductors or circuit parts. Many technicians believe that troubleshooting is not “working on.” Clearly, it is, and appropriate PPE is necessary.

The second sentence states there are two categories of working on: diagnostic (testing) and repair. Diagnostic is defined as “taking readings or measurements of electrical equipment with approved test equipment that does not require making any physical change to the equipment.” This includes absence-of-voltage testing, troubleshooting, calibration, or voltage testing. Again, PPE is mandatory because using voltage-rated probes on energized electrical equipment is not considered safe. There is an exception in Chapter 3 for laboratory work, but it would not apply to NETA-type work. Article 350 applies to this work where a specifically trained and responsible person known as the electrical safety authority (ESA) can make job-specific requirements that may be different than those found in Chapter 1.

The second category of working on (repair) is defined as “any physical alteration of electrical equipment (such as making or tightening connections, removing or replacing components, etc.). We have seen many instances where this is misunderstood or just violated, especially during maintenance-type activities.

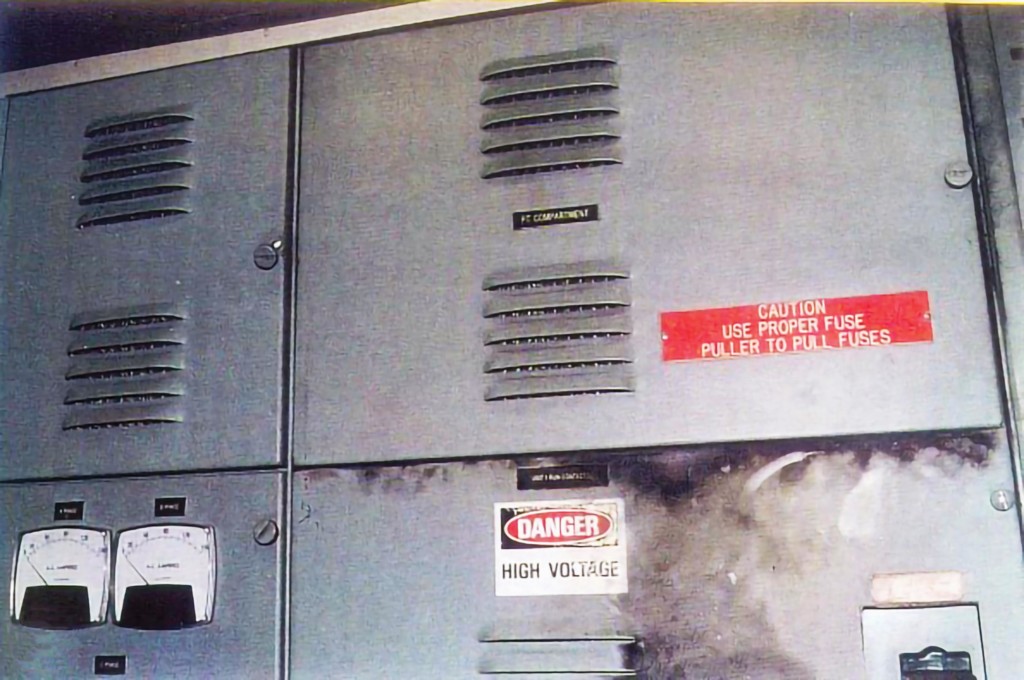

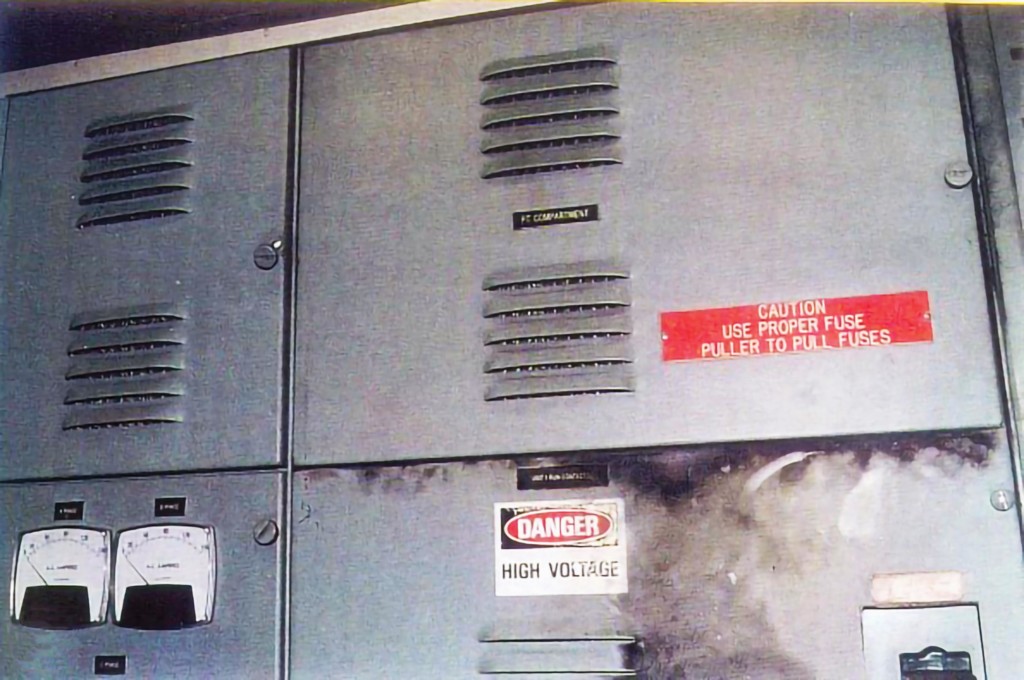

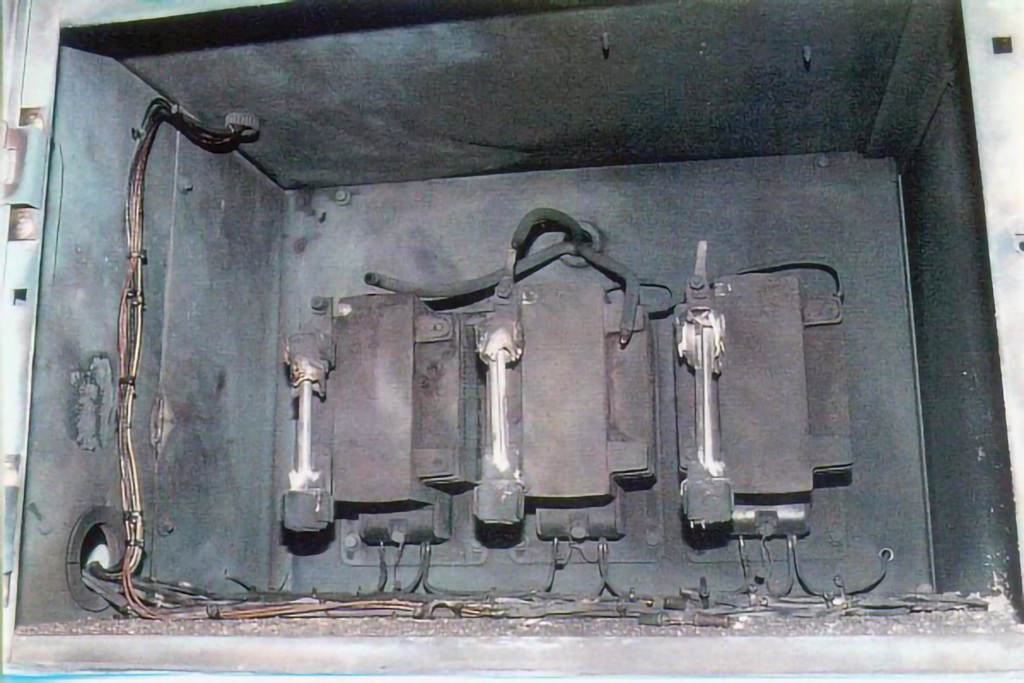

Figure 2: PT Compartment

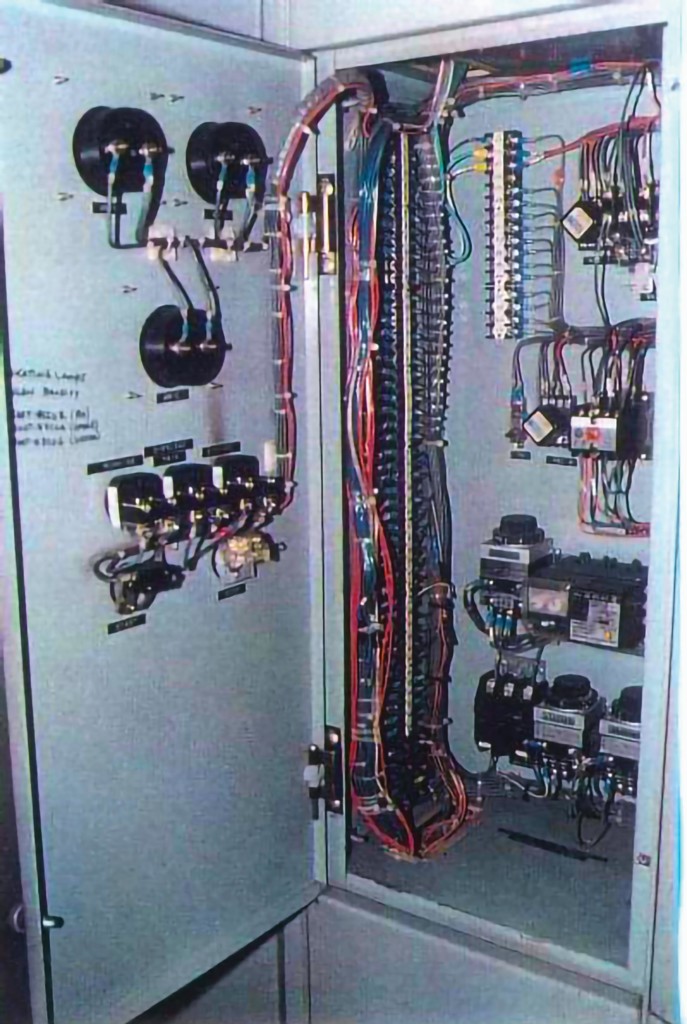

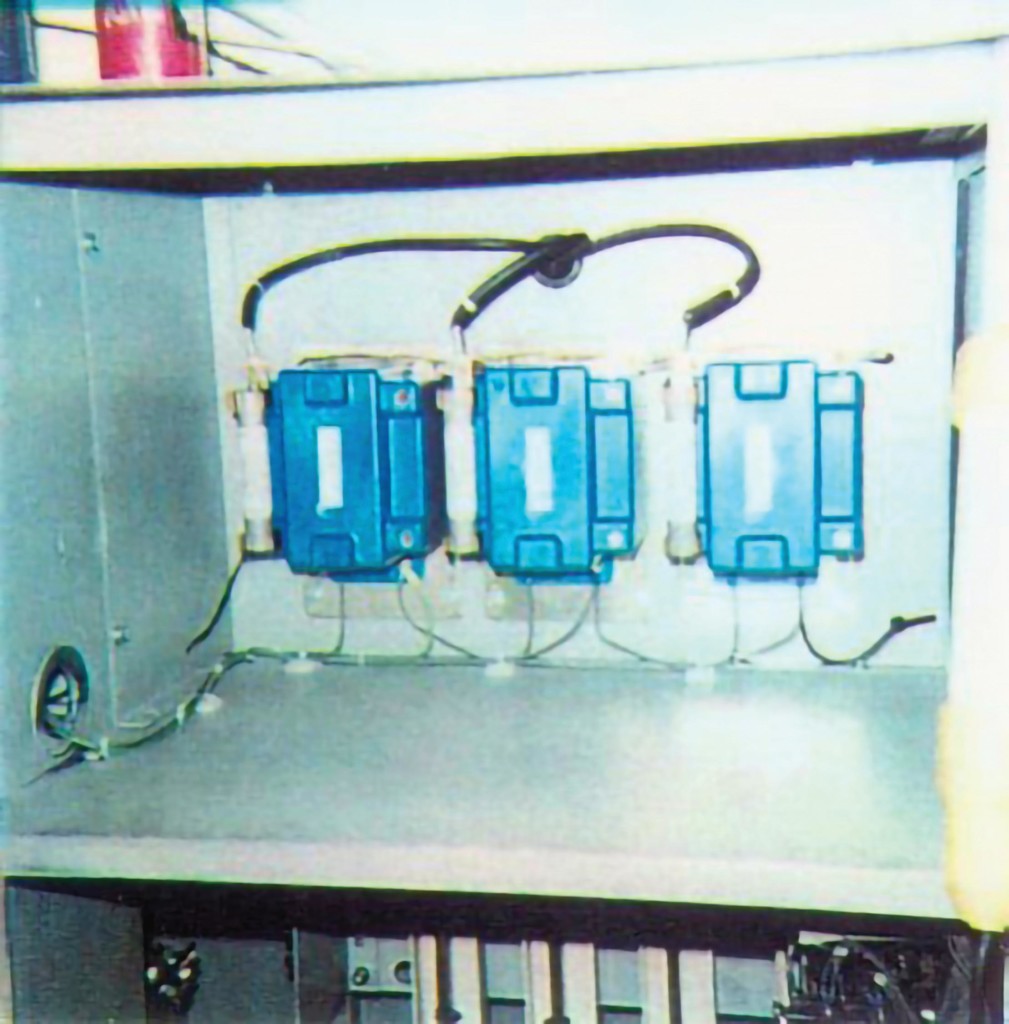

True story: A job leader took an apprentice to a switchgear room where low- and high-voltage equipment was installed. He pointed out areas the apprentice was to avoid, such as the main incoming line compartment. He worked with the apprentice for some time cleaning low-voltage connection strips and cleaning the inside of the panels. The job leader was called away to another part of the job. He told the apprentice, “Don’t work on anything that looks hot,” and walked away. The apprentice cleaned, tightened connections, and inspected the low-voltage control compartments. In each compartment, he used his voltmeter to determine whether the terminals were energized (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Work Area

He came to the compartment containing 4160 V potential transformers. This compartment was marked PT Compartment, but it did not have a sign on it warning of high voltage. The compartment immediately below the PT compartment did have a DANGER HIGH VOLTAGE sign on the top of its compartment door (Figure 2).

Figure 2: PT Compartment

The apprentice opened the door without the warning sign and attempted to test the terminals of the 4160 V PTs. There was no indication of danger to the technician (Figure 3).

Figure 3: PTs Look Innocent

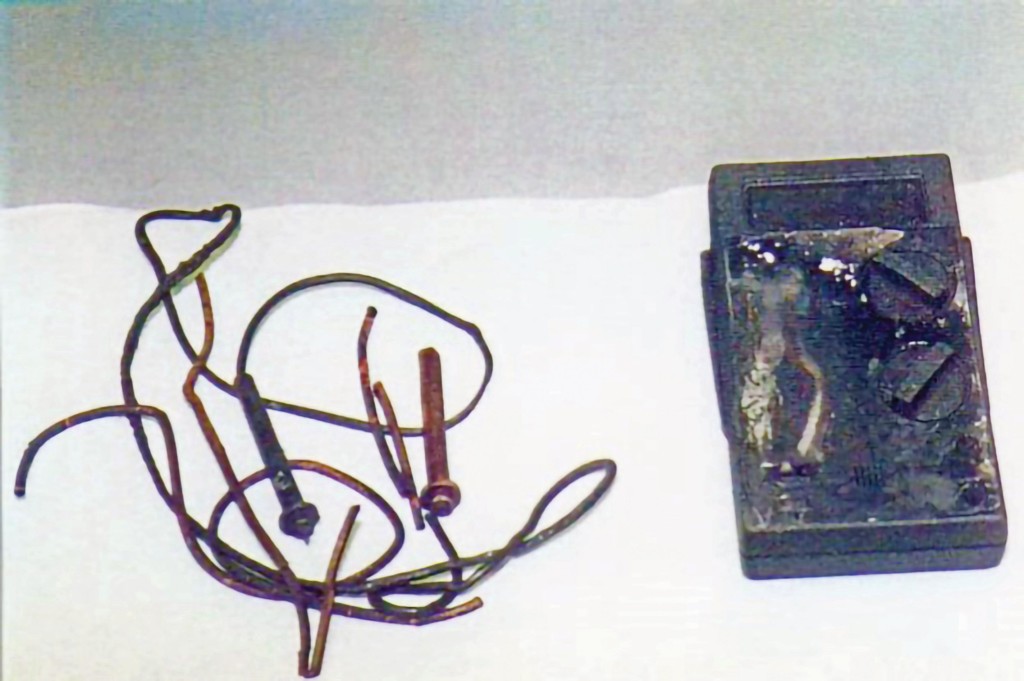

As soon as the test probes touched the PTs, an arc flash occurred. The apprentice was fortunate, as he survived the incident, but he spent several days in the hospital’s burn unit. He could have very well died, as he was not wearing any PPE. Figure 4 shows the aftermath of the PTs blowing up, while Figure 5 shows the low-voltage tester used to test 4160 V PTs. Not good. This case history, “Who’s at Fault — Owner or Contractor?” was presented to the 2002 IEEE Electrical Safety Workshop by Joseph Andrews.

Figure 4: Remains of the PTs

Figure 5: Remains of the Incorrect Voltage Tester

This example shows why the 70E definitions are so critical. What people don’t know, they don’t know. Much useful information is contained in the definitions. You may feel there is no danger using an insulated (or uninsulated) screwdriver to tighten connections or in using a voltage tester to perform absence-of-voltage testing. but there could be danger lurking just around the corner.

Chapter 1, Article 130, Section 130.2(B)(3) provides exceptions to the use of an energized electrical work permit. The entire section is reproduced below:

Δ (3) Exemptions to Work Permit. Electrical work shall be permitted without an energized electrical work permit if a qualified person is provided with and uses appropriate safe work practices and PPE in accordance with Chapter 1 under any of the following conditions:

- Testing, troubleshooting, or voltage measuring

- Thermography, ultrasound, or visual inspections if the restricted approach boundary is not crossed

- Access to and egress from an area with energized electrical equipment if no electrical work is performed and the restricted approach boundary is not crossed

- General housekeeping and miscellaneous non-electrical tasks if the restricted approach boundary is not crossed

The triangle (Δ) indicates a change has taken place from the last 70E edition. Note that the first sentence says, “Electrical work shall be permitted without an energized electrical work permit if a qualified person is provided with and uses appropriate safe work practices and PPE in accordance with Chapter 1 under any of the following conditions.” The person must be qualified to begin with. Unqualified persons are not permitted to be near energized electrical conductors or circuit parts. Second, that qualified person must be provided with and use appropriate safe work practices and PPE. An unqualified person would not know or be able to determine what is appropriate. The person in the case history above could not determine those two things.

Conclusion

Supervisors at any level — whether it’s in their title or not — must not make assumptions about what a person knows or doesn’t know. They must ensure the technician’s safety. Troubleshooting, testing, and even tightening connections are considered by many to be safe. The previous example shows how wrong that assumption can be — and it is not just apprentices who make that mistake. Troubleshooting the control power transformer on a 4160 V motor starter has caused many incidents. One technician told me how the guts of his wiggy (he was pretty old) flew across a building, striking 15 feet high on the opposite wall. If that coil had hit him, he would have been severely injured or killed. With electricity, small mistakes can be painful or fatal.

Ron Widup and Jim White are NETA’s representatives to NFPA Technical Committee 70E, Electrical Safety Requirements for Employee Workplaces. Both gentlemen are employed by Shermco Industries in Dallas, Texas, a NETA Accredited Company.

Ron Widup, Shermco Industries Vice Chairman and Senior Advisor, Technical Services, has been with Shermco since 1983, and currently serves on the company’s board of directors. He is a member of Technical Committee on NFPA 70E, Electrical Safety in the Workplace; a Principal Member of National Electrical Code (NFPA 70) Code Panel 11; a Principal Member of the Technical Committee on NFPA 790, Standard for Competency of Third-Party Evaluation Bodies; a Principal Member of the Technical Committee on NFPA 791, Recommended Practice and Procedures for Unlabeled Electrical Equipment Evaluation; a member of the Technical Committee on NFPA 70B, Recommended Practice for Electrical Equipment Maintenance, and Vice Chair for IEEE Std. 3007.3, Recommended Practice for Electrical Safety in Industrial and Commercial Power Systems. Ron also serves on NETA’s board of directors and Standards Review Council. He is a NETA Certified Level 4 Senior Test Technician, a State of Texas Journeyman Electrician, an IEEE Standards Association member, an Inspector Member of the International Association of Electrical Inspectors, and an NFPA Certified Electrical Safety Compliance Professional (CESCP).

Ron Widup, Shermco Industries Vice Chairman and Senior Advisor, Technical Services, has been with Shermco since 1983, and currently serves on the company’s board of directors. He is a member of Technical Committee on NFPA 70E, Electrical Safety in the Workplace; a Principal Member of National Electrical Code (NFPA 70) Code Panel 11; a Principal Member of the Technical Committee on NFPA 790, Standard for Competency of Third-Party Evaluation Bodies; a Principal Member of the Technical Committee on NFPA 791, Recommended Practice and Procedures for Unlabeled Electrical Equipment Evaluation; a member of the Technical Committee on NFPA 70B, Recommended Practice for Electrical Equipment Maintenance, and Vice Chair for IEEE Std. 3007.3, Recommended Practice for Electrical Safety in Industrial and Commercial Power Systems. Ron also serves on NETA’s board of directors and Standards Review Council. He is a NETA Certified Level 4 Senior Test Technician, a State of Texas Journeyman Electrician, an IEEE Standards Association member, an Inspector Member of the International Association of Electrical Inspectors, and an NFPA Certified Electrical Safety Compliance Professional (CESCP).

James (Jim) R. White, Vice President of Training Services, has worked for Shermco Industries since 2001. He is a NFPA Certified Electrical Safety Compliance Professional and a NETA Level 4 Senior Technician. Jim is NETA’s principal member on NFPA Technical Committee NFPA 70E®, Electrical Safety in the Workplace; NETA’s principal representative on National Electrical Code® Code-Making Panel (CMP) 13; and represents NETA on ASTM International Technical Committee F18, Electrical Protective Equipment for Workers. Jim is Shermco Industries’ principal member on NFPA Technical Committee for NFPA 70B, Recommended Practice for Electrical Equipment Maintenance and represents AWEA on the ANSI/ISEA Standard 203, Secondary Single-Use Flame Resistant Protective Clothing for Use Over Primary Flame Resistant Protective Clothing. An IEEE Senior Member, Jim was Chairman of the IEEE Electrical Safety Workshop in 2008 and is currently Vice Chair for the IEEE IAS/PCIC Safety Subcommittee.

James (Jim) R. White, Vice President of Training Services, has worked for Shermco Industries since 2001. He is a NFPA Certified Electrical Safety Compliance Professional and a NETA Level 4 Senior Technician. Jim is NETA’s principal member on NFPA Technical Committee NFPA 70E®, Electrical Safety in the Workplace; NETA’s principal representative on National Electrical Code® Code-Making Panel (CMP) 13; and represents NETA on ASTM International Technical Committee F18, Electrical Protective Equipment for Workers. Jim is Shermco Industries’ principal member on NFPA Technical Committee for NFPA 70B, Recommended Practice for Electrical Equipment Maintenance and represents AWEA on the ANSI/ISEA Standard 203, Secondary Single-Use Flame Resistant Protective Clothing for Use Over Primary Flame Resistant Protective Clothing. An IEEE Senior Member, Jim was Chairman of the IEEE Electrical Safety Workshop in 2008 and is currently Vice Chair for the IEEE IAS/PCIC Safety Subcommittee.