Becoming a great company doesn’t happen overnight. Instead, it is about small, incremental steps as we progress down the road of becoming better and better at what we do and how we do it.

This is the most critical as it relates to our safety processes and safety culture. It is important to note that the first step in making a situation safer is to engineer the hazard out of it; the last step is to use PPE.

Technology also plays a huge role, but at the end of the day, it is often an individual’s decisions and actions that lead to an incident. Unfortunately, humans will make mistakes regardless of how many processes, procedures, and rules companies implement. These mistakes can lead to damaged equipment and injury to the individual or someone else. So, what can we do?

One tool we use is to put a giant red or yellow flag figuratively and literally in front of people’s faces. Human performance improvement (HPI) methods are a way of alerting someone regardless of whether they are an inexperienced junior technician or a senior technician who may have become complacent to the fact that a step must be taken before moving forward with a task. HPIs help with common hazards from slips, trips, and falls all the way to catastrophic incidents such as leaving ground chains applied during energization or working on a live current transformer (CT) circuit.

The goal of this discussion is to share some best practices from the field and provide the reader with the opportunity to think critically about using HPIs within their organization as a way to continually improve safety and efficiency.

BARRIERS

The first example is a high-voltage substation where the team is following required safe work methods by, among other steps, installing barriers (Figure 1 and Figure 2) in places where live CTs and in-service protections are energized.

Figure 1: Front of Protection and Control Racks in a High-Voltage Substation

Figure 2: Rear of Protection and Control Racks in a High-Voltage Substation

This physical barrier allows technicians to easily flag the location where the work is to take place by covering nearby modules, racks, etc. This greatly reduces the chance of technicians mistakenly working on modules that are outside the work zone or isolations. It also minimizes the likelihood of opening live CT secondaries, which can cause serious injury or death as well as major damage to equipment and systems.

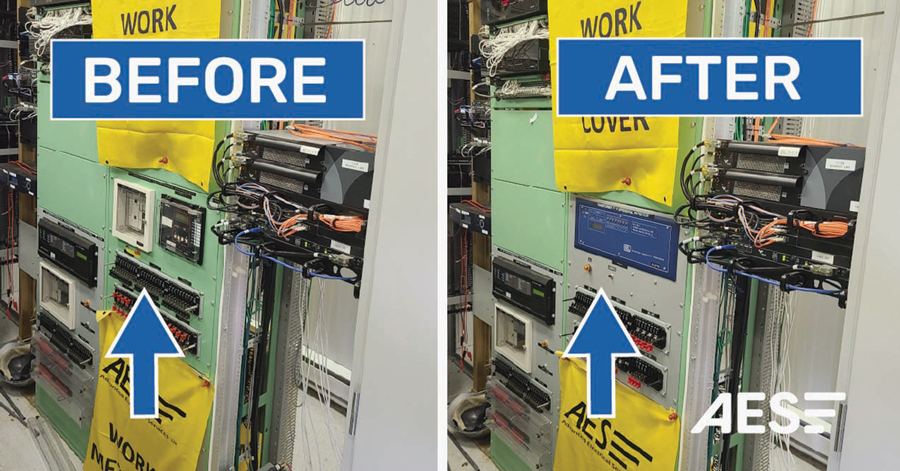

All CT circuits in the uncovered modules are verified for zero current prior to work starting. In addition to assuring personnel safety, it reduces the chance of tripping any in-service equipment as these modules are covered up (Figure 3), and improves efficiency as the work locations are obvious and clearly marked. The absence of voltage and current can be verified based on isolations including guarantee of isolation (GOI), clearance, and lockout, and live terminals can be flagged or taped off. This must remain consistent throughout the work.

Figure 3: Before and After a Protection & Control Relay Upgrade Project

When work must be performed on flagged racks, these methods remind technicians that terminals must be checked for voltage and current since this has not previously been verified. Unfortunately, there have been too many incidents where a technician or electrician is exposed to an arc flash or electric shock from working in the wrong location after a lunch break, shift change, or days off. HPI steps like this are critical to continuous improvement within a safety system, and we must make it a priority to reduce or eliminate this hazard.

VEHICLE HAZARDS

One of the biggest causes of workplace injuries is slips, trips, and falls, which can occur more often when exiting vehicles during inclement weather. At the same time, crashes and collisions while driving, regardless of the industry, continue to be a leading cause of injuries. To address these issues, we have implemented an HPI for 360-degree vehicle walk-arounds (Figure 4) to be completed when entering and exiting a vehicle. The goal is simple but critical: Reduce slips when entering and exiting, make sure the vehicle is safe to drive, and ensure no one will be hurt when the vehicle moves.

Figure 4: Steering-Wheel Cover

Yellow steering-wheel covers (Figure 4) with a message remind our drivers to always use three points of contact when entering or exiting the vehicles. To ensure safety for those around our vehicles, drivers are reminded to do a complete 360-degree walk-around before operating the vehicle. Additional precautions could include placing a cover on the passenger-side mirror as a reminder to walk around the vehicle. To supplement the walk-around process, our team uses a safety app to complete an online checklist that documents and submits their findings for future review and audits.

HPI AND NETA

Where can HPIs be used in the NETA service world?

- Remove ground chains prior to energization.

- Record “as left” and “as found” settings of relays and breakers during a maintenance turnaround.

- Remove and re-terminate leads, i.e., remove transformer leads for testing.

- Erect red flags or physical barriers in front of equipment that may still be energized during maintenance.

OTHER HAZARDS

What other hazards or injuries can HPIs address? A great starting point would be to look at what could have stopped an incident or near miss from occurring and implement an HPI so it does not happen again. Additionally, it may make sense for your organization to start with the most common workplace incidences:

- Slips, trips, and falls

- Muscle strains

- Repetitive strains

- Crashes and collisions

- Cuts and lacerations

- Inhaling toxic fumes

- Exposure to loud noise

- Walking into objects

In fiscal year 2020 (October 1, 2019, through September 30, 2020), these 10 OSHA standards were cited most frequently:

- Fall Protection, Construction 29 CFR 1926.501, www.osha.gov/fall-protection.

- Hazard Communication Standard, General Industry 29 CFR 1910.1200,

www.osha.gov/hazcom. - Respiratory Protection, General Industry 29 CFR 1910.134,

www.osha.gov/respiratory-protection. - Scaffolding, General Requirements, Construction 29 CFR 1926.451,

www.osha.gov/scaffolding. - Ladders, Construction 29 CFR 1926.1053, www.osha.gov/fall-protection.

- Control of Hazardous Energy (Lockout/Tagout), General Industry 29 CFR 1910.147, www.osha.gov/control-hazardous-energy.

- Powered Industrial Trucks, General Industry 29 CFR 1910.178, www.osha.gov/powered-industrial-trucks.

- Fall Protection, Training Requirements 29 CFR 1926.503, www.osha.gov/fall-protection.

- Eye and Face Protection 29 CFR 1926.102, www.osha.gov/eye-face-protection.

- Machinery and Machine Guarding, General Requirements 29 CFR 1910.212, www.osha.gov/machine-guarding.

Editor’s Note: Watch for OSHA’s 2021 report soon after April 1, 2022.

CONCLUSION

Human performance improvements can be a great auditing tool. It can be difficult during a site safety audit to know, for example, whether the crew knew whether equipment was energized or not energized. However, if an energized area should have been covered and it was not, you have a red flag that more training is required. In the case of an HPI like the steering wheel cover, it is either on or off.

Whether the HPI is a traditional barrier or a visual reminder, the intent is to force a critical step in the sequence of events. The goal of this forced step is to break the chain of events that might have led to an incident. In addition to creating a safer company, HPIs can also contribute to making it more profitable.

REFERENCES

[1] Work Safety Blog. “10 of the Most Common Workplace Accidents and Injuries,” Accessed at 10 of the Most Common Workplace Accidents and Injuries | Work Safety Blog (blog4safety.com).

[2] OSHA. “Top 10 Most Frequently Cited OSHA Standards Violated in FY2020.” Available at www.osha.gov/data/commonstats.

Matt Eakins is the Technical Services Manager at Advanced Electrical Services Ltd. He has 12-plus years of experience testing and commissioning in the industrial and utility sectors of Western Canada. Matt is a NETA Level 3 Technician and an ASET CET who studied electronics engineering at the RCC Institute of Technology (Concord, Ontario) as well as electrical techniques at Loyalist College (Bellville, Ontario). Matt began his career with AES in 2009; he is now responsible for managing medium- to large-scale electrical commissioning and maintenance projects for AES’s many clients across Western Canada.

Matt Eakins is the Technical Services Manager at Advanced Electrical Services Ltd. He has 12-plus years of experience testing and commissioning in the industrial and utility sectors of Western Canada. Matt is a NETA Level 3 Technician and an ASET CET who studied electronics engineering at the RCC Institute of Technology (Concord, Ontario) as well as electrical techniques at Loyalist College (Bellville, Ontario). Matt began his career with AES in 2009; he is now responsible for managing medium- to large-scale electrical commissioning and maintenance projects for AES’s many clients across Western Canada.