In today’s rapidly evolving industrial landscape, ensuring the reliable operation and safety of electrical systems is crucial. More than ever, facility managers and businesses must prioritize regular maintenance, testing, and repairs to prevent hazards to equipment and personnel as well as costly downtime.

Over the years, convincing clients of the importance of these electrical maintenance services has met various challenges, depending on the organization’s culture. One tool to initiate maintenance, testing, and repair business has been to utilize the National Fire Protection Association’s NFPA 70B, Standard for Electrical Equipment Maintenance, as a recommended practice. Much like many other recommendations, implementation was done at the discretion of each individual facility or at the encouragement of insurance companies. With the release of NFPA 70B–2023, many of the recommended best practices have become mandated standards that electrical power consumers must implement in their facilities.

NETA members have been among the many organizations that have contributed to this new milestone for NFPA 70B. Dave Huffman is one of NETA’s NFPA 70B panel representatives. One of his important observations is that this is a consensus standard where all parties needed to work together, which required all to compromise. “The assembled group worked together and concentrated on the goal of creating a document that was focused on the mission of increasing electrical power system safety,” says Huffman.

WHAT HASN’T CHANGED FOR NFPA 70B

For many decades, NFPA 70B has been a source of information and guidance related to the value of electrical preventative maintenance (EPM) of electrical power systems to mitigate risks and liabilities. NFPA has long recognized that the majority of industrial fires are electrical in nature. Practices meant to prevent fires also have the benefit of increasing system safety and reliability. NFPA 70B compliance not only enhances safety but also helps facilities reduce their liability exposure. In the event of an accident or electrical failure, businesses adhering to NFPA 70B guidelines are better protected legally and financially, as they can demonstrate that they took the recommended (now required) necessary steps to ensure safety and mitigate potential risks.

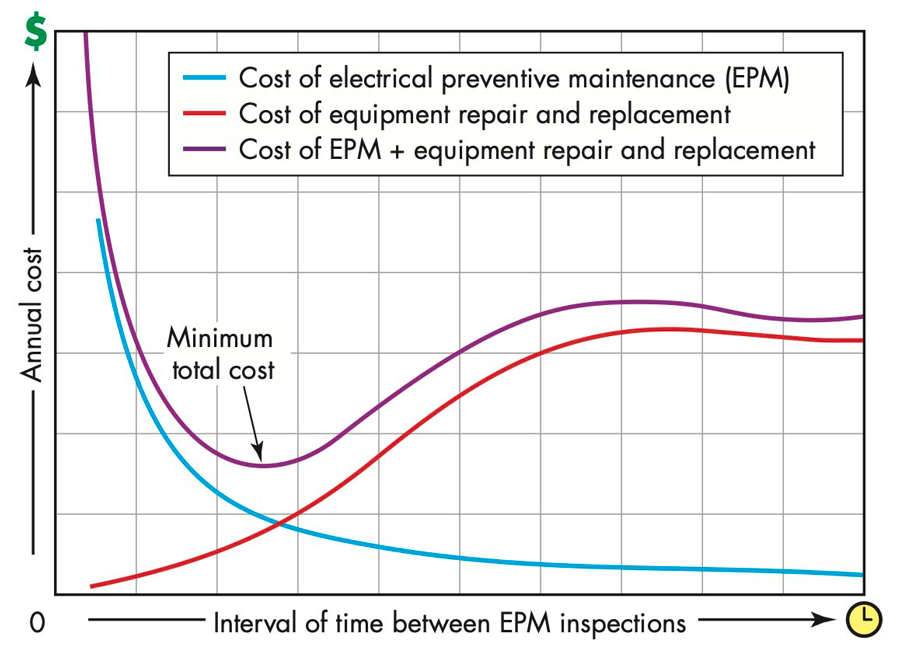

The chart of annual costs versus time intervals between EPM inspections demonstrates the overall value of EPM as opposed to the run-to-failure model. The basic idea is that there is a minimum total cost that can be achieved by performing EPM. However, the chart doesn’t go beyond the cost of equipment damage to consider the additional costs to the facility related to the downtime. Obviously, the cost of failure can vary greatly between facilities — their production, process, or impact on client service disruption. It is also important to note that the chart doesn’t attempt to address the cost of potential injuries to personnel that could occur during a failure.

One common challenge when working with a variety of facilities is the inability to document the value of failures and injuries that didn’t happen. This challenge to sell the invisible has led to many facilities continuing to operate with minimal or no EPM, only dealing with failures as they occur. Proactive measures can detect and address issues early on, preventing minor problems from escalating into major failures that could lead to extensive downtime, expensive repairs, and injuries. Over time, making NFPA 70B a standard will evolve the discussion as failures could now carry fines from OSHA because of the direct impact that ignoring maintenance has on electrical system safety.

Reproduced with permission of NFPA from NFPA 70B, Standard for Electrical Equipment Maintenance, 2019 edition. Copyright©2018, National Fire Protection Association. For a full copy of NFPA 70B, please go to www.nfpa.org.

WHAT’S IMPORTANT TO KNOW ABOUT NFPA 70B AS A STANDARD

NFPA 70B and NFPA 70E specify the guidelines for OSHA 29 CFR 1910.132, 269, and 331-335 and OSHA 29 CFR 1926.28. Prior to 2023, 70B was a guide; now it has been elevated to an ANSI standard, and with that comes increased importance and mandatory action. NFPA 70B is designed to work in conjunction with the state-adopted NFPA 70, National Electrical Code (NEC), for installation of electrical systems and with NFPA 70E, Standard for Electrical Safety in the Workplace. Unlike the NEC, NFPA 70B is not a code or directly mandated by law. Similar to NFPA 70E, 70B is considered the minimum consensus standard for the maintenance of electrical systems.

For many years, OSHA has used 70E to enforce OSHA 1910.331-335. The fact that NFPA 70E refers to 70B as well as other industry standards regarding the need for periodic maintenance to support an electrical system implies that proper maintenance will also become enforceable. Ultimately, these standards work together to ensure that equipment is properly installed (NEC), that it is maintained to a minimum criteria (NFPA 70B) over its lifetime, and that all of this work is performed in a safe manner (NFPA 70E).

CHAPTER 4 GENERAL (ELECTRICAL PREVENTIVE MAINTENANCE PROGRAMS)

The language in NFPA 70B is now prescriptive: Facilities shall create an electrical maintenance program (EMP). NFPA 70B Section 4.2 provides defined requirements for the elements the EMP shall include:

- An electrical safety program that addresses the condition of maintenance

- Identification of personnel responsible for implementing each element of the program

- Survey and analysis of electrical equipment and systems to determine maintenance requirements and priorities.

- Developed and documented maintenance procedures for equipment

- A plan of inspections, servicing, and suitable tests

- A maintenance, equipment, and personnel documentation and records-retention policy

- A process to prescribe, implement, and document corrective measures based on collected data

- A process for incorporating design for maintainability in electrical installations

- A program review and revision process that considers failures and findings for continuous improvement

Many readers also understand that electrical maintenance programs are best when there is regular feedback into the program for improvement. Section 4.2.6, while titled Incident Investigations, serves as that feedback and refinement loop. This is where the facility and those they depend on for the execution of the EMP shall provide the following input:

- Electrical safety incidents

- Equipment malfunctions

- Unintended operations or alarms

- Operation of protective devices

The inclusion of this information is a powerful step to avoiding the almost imperceptible temptation to normalize equipment deviation from standards. The normalization of deviation leads to a myriad of safety and operation issues. Everything from simple equipment malfunctions like indicating lights not operating to known equipment issues like a breaker not racking in or out smoothly shall now be documented for corrective action.

CHAPTER 6 SINGLE-LINE DIAGRAMS AND SYSTEM STUDIES

The most recent version of NFPA 70E provided guidance that shall be reviewed every five years. In NFPA 70B, the following studies have a mandatory interval, not to exceed five years, to review them for accuracy:

- Section 6.3 – Short-circuit studies

- Section 6.4 – Coordination studies

- Section 6.7 – Incident energy analyses

Even with the five-year requirement, system owners need to understand the importance of performing and updating studies when major system modifications are made. A utility transformer replacement or upgrade from a fused bolted pressure switch to a modern insulated case breaker replacement are critical changes to be modeled and changes applied to the protective device settings for the safety of personnel and equipment.

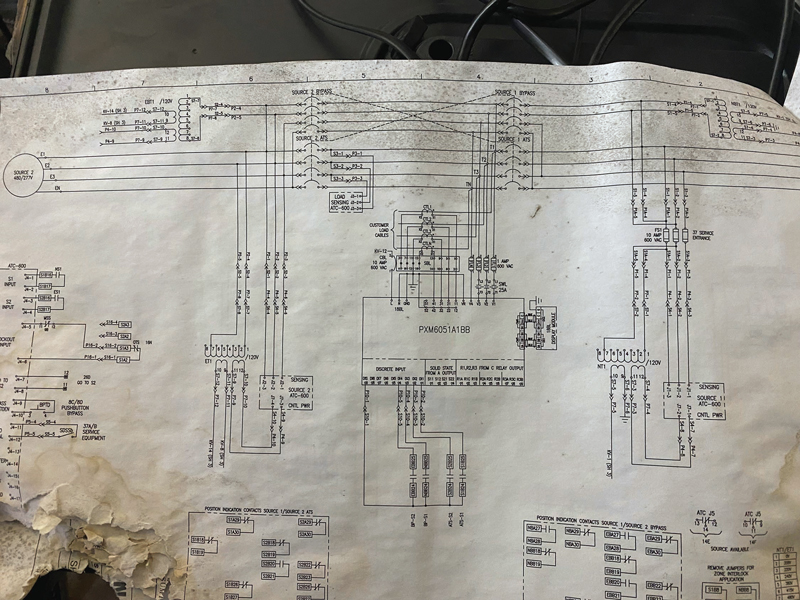

An important aspect of the system studies process is legible, accurate, and up-to-date single-line drawings (Figure 2). It can’t be overstated that electricians and technicians depend on this most basic of tools to properly understand and safely interact with a facility’s power system.

Lack of accurate, legible, and up-to-date drawings is one of the more common ways that a facility will slowly normalize deviation over time. It’s not intentional; it happens one circuit and one panel at a time.

CHAPTER 8 FIELD TESTING AND TEST METHODS

Chapter 8 now contains additional specificity defining testing category types. Section 8.3 lists:

Category 1. Online standard test – Performed while the electrical equipment or device is connected to the source of supply. These inspections would include items like visual and thermographic inspections.

Category 1A. Online enhanced test – Not typically performed in normal electrical maintenance activities and provides additional diagnostic information. Technology continues to evolve and allows facilities to gain more information about their power system while energized. This can include continuous equipment temperature, online partial discharge, and dissolved gas in transformer oil to name a few. These enhancements can be utilized to extend the periodicities discussed in Chapter 9 by gaining new insight into the equipment condition while online.

Category 2. Offline standard test – Performed while the electrical equipment or device is disconnected from the source of supply or is connected to an external test voltage source of supply. These tests are the typical component testing, examples are TTR of a transformer or insulation resistance test of a switchboard, which many facilities are performing on a variety of components and timeframes.

Category 2A. Offline enhanced test – Typically not required testing that may be useful based on the application of the equipment or if there is a problem with the equipment. For example, a “rated hold-in” test in accordance with NEMA AB-4 might be performed on a molded case circuit breaker if the circuit breaker has been tripping under normal load conditions. It is important to note that NFPA 70B provides the minimum requirements for preventive maintenance, which are superseded by manufacturer guidelines.

CHAPTER 9 MAINTENANCE INTERVALS

Much like ANSI/NETA MTS provides Appendix B with recommended testing periodicities based on equipment condition and criticality, NFPA 70B Table 9.2.2 provides additional guidance. It is important to note that neither ANSI/NETA MTS nor NFPA 70B supersede the manufacturer’s recommendations. To clarify that statement: If a manufacturer states that a piece of equipment should be maintained annually, and NFPA 70B specifies maintenance every 36 months, the manufacturer’s guidance must be followed.

Of particular importance are the condition assessment criteria and the role they play in the recommended frequency of testing. One example of how the condition assessment can impact testing intervals is for power circuit breakers: Circuit breakers in Condition 1 can undergo testing intervals of up to 60 months. In contrast, circuit breakers in Condition 3 would require annual service.

Three factors drive condition assessment:

- Physical Condition of Electrical Equipment – Section 9.3.1

a. Condition 1 Equipment:

i. Appears in like-new condition.

ii. The enclosure is clean, free of moisture, and tight.

iii. There are no unaddressed notifications from continuous monitoring systems.

iv. There are no active recommendations from predictive techniques.

v. Previous maintenance is in accordance with EMP.

b. Condition 2 Equipment:

i. Maintenance results deviate from past results or have indicated more frequent maintenance.

ii. The previous maintenance cycle has revealed issues requiring the repair or replacement of the major equipment components.

iii. There are active recommendations from predictive technologies or notifications from continuous monitoring systems.

c. Condition 3 Equipment:

i. The equipment has missed the last two cycles in accordance with the EMP.

ii. Urgent actions were identified from predictive technologies. - Criticality Condition of Equipment – Section 9.3.2

a. Condition 1 or 2 can be assigned if failure will not endanger personnel.

b. Condition 3 must be assigned if failure can cause injury to a worker. - Operating Environment Condition of Equipment – Section 9.3.3

a. Condition 1 or 2 can be assigned if the equipment is rated for the environment in which it is installed. An example is a NEMA 4 enclosure where subject to hose-down conditions.

b. Condition 3 must be assigned when equipment is in a harsh environment for which it is not rated.

It should be noted that some operating environments — such as harsh chemicals and contaminants — can cause accelerated damage to equipment even if the equipment is properly rated.

The final condition assessment is based on the highest of any one of the categories above. For example, if equipment is in physical Condition 1 and operating in a Condition 3 environment, then Condition 3 periodicity would guide maintenance periodicity. An interesting and subjective question arises when it comes to the criticality condition. Much of the equipment in an electrical system is interacted with by qualified workers on an almost daily basis. With that mental framework, it could be argued that all equipment of sufficient incident energy level could be rated Condition 3. This criticality condition will be an area for additional committee input, development, and debate as facilities work to balance the now-required EMP against available budgets and production outage windows.

CHAPTERS 11–38 EQUIPMENT TESTING TASKS

NFPA 70B has greatly improved and added information related to the inspections and testing that must be accomplished on electrical equipment. These chapters break down testing that is required in a similar fashion to ANSI/NETA MTS. Differences do exist as there are no pass/fail or evaluation criteria results. To help avoid confusion, should you review these chapters, you will see Category 2A task requirements. One example is in Chapter 12 Substations and Switchgear, where you will find a 2A task to “measure insulation resistance of control wiring.” This test is considered optional in ANSI/NETA MTS and not necessarily required unless there are concerns about the equipment.

Chapter 15

Chapter 15 Circuit Breakers, Low and Medium Voltage is sure to inspire some spirited debate between NETA testing companies, clients, and manufacturers, particularly the example of molded case circuit breakers (MCCB) where breakers less than 250 amperes are listed as Category 2A (optional) for testing contact and insulation resistance, and breakers greater than 250 amperes are Category 2 (required) for testing. This chapter also states that the primary current testing of trip functions is Category 2A (optional) for circuit breakers 250 A or less and for circuit breakers with electronic trip units. This means that primary current testing of breakers greater than 250 A with electronic trip units is considered optional and may be tested by means of the manufacturer’s specified (secondary injection) test sets.

Chapters 30 through 33 address the growing sectors of solar and wind power generation as well as electric vehicle charging and battery storage.

CONCLUSION

Leveraging NFPA 70B offers a multitude of advantages to facilities dedicated to the safety and reliability of their power systems. The ultimate objective should be to foster a culture of maintenance commitment rather than mere compliance. Facilities that view electrical preventative maintenance solely through the lens of regulatory compliance risk overlooking the substantial benefits that can be gained. Wholehearted dedication to this industry standard elevates a business’s reputation as a dependable and safety-conscious partner.

Recognizing the complexity of implementing new programs or enhancing existing ones, many facilities will find valuable support from InterNational Electrical Testing Association (NETA) companies in crafting and executing effective electrical preventative maintenance programs while contributing to a safer and more efficient industrial landscape.

Mose Ramieh is Vice President of Business Development at CBS Field Services. A former Navy man, Texas Longhorn, Vlogger, CrossFit enthusiast, and slow-cigar-smoking champion, Mose has been in the electrical testing industry for more than 25 years. He is a Level IV NETA Technician with an eye for simplicity and utilizing the KISS principle in the execution of acceptance and maintenance testing. Over the years, he has held positions at four companies ranging from field service technician, operations, sales, business development, and company owner. To this day, he claims he is on call 24/7/365 to assist anyone with an electrical challenge. That includes you, so be sure to connect with him on the socials.